Recent News

WWE Is Laying the Smackdown on the World

World Wrestling Entertainment is setting revenue records with a prescient network strategy and a new generation of female and international stars.

The building that houses the headquarters of World Wrestling Entertainment Inc. stands just off Interstate 95 in Stamford, Conn. Its facade is vaguely menacing, a curtain of black glass topped by a Jolly Rogeresque black flag. Inside the lobby, visitors pass by a life-size statue of Andre the Giant, the 7-foot-4-inch, 520-pound superstar of yesteryear. It’s a sensation not unlike strolling under the vast basilica of a Roman temple. Welcome to this divine space, ye slight-statured mortal.

On a Friday afternoon in December, Stephanie McMahon, WWE’s chief brand officer, is seated in her office on the top floor. She’s dressed in black, with earrings shaped like daggers. Near her desk is a football signed by New England Patriots tight end Rob Gronkowski, who last year brandished his meaty deltoids in the ring at WrestleMania 33.

The market’s enthusiasm for WWE stems largely from its lucrative TV contracts, combined with its early success in direct-to-consumer streaming TV apps. In 2014 the company made a risky move, deciding essentially to cannibalize its traditional pay-per-view business. Instead of paying their cable companies one-time fees to see WWE’s marquee events—say, $44.99 for the Royal Rumble—fans would be encouraged to subscribe to a streaming video service, the WWE Network, and pay a monthly fee. After some early turbulence, the move is paying off. Roughly 1.5 million people now hand over $9.99 a month for the WWE Network, making it the 11th-most-popular streaming video service in the U.S., according to Parks Associates, and the second-most-popular, after Major League Baseball’s, in the “sports-related” category.

McMahon, 41, is the scion of a pro wrestling dynasty. Her grandfather and great-grandfather were influential promoters in the industry’s early years. During the latter half of the 20th century, her father, Vince McMahon, WWE’s chairman and chief executive officer, transformed the family business from a niche regional attraction into a mainstream brand whose stars—Hulk Hogan, Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson, John Cena, Dave Bautista—regularly graduate to Hollywood careers.

“There was a time when it came across as seedy, kind of playing to barroom brawls,” McMahon says. Those days are over, she asserts. “Our lines of business are really more akin to Disney than they are to anything else.”

McMahon is both executive and on-screen performer for WWE. She used to play the boss’s entitled, imperious daughter; now she’s a rancorous commissioner, endlessly bickering with the family’s brawny help. In 2003 she married Paul Levesque, a WWE star who wrestles as Triple H. He’s since joined his wife in the executive ranks, forming the rare media power couple capable of deploying both beatdowns and Chartbeat.

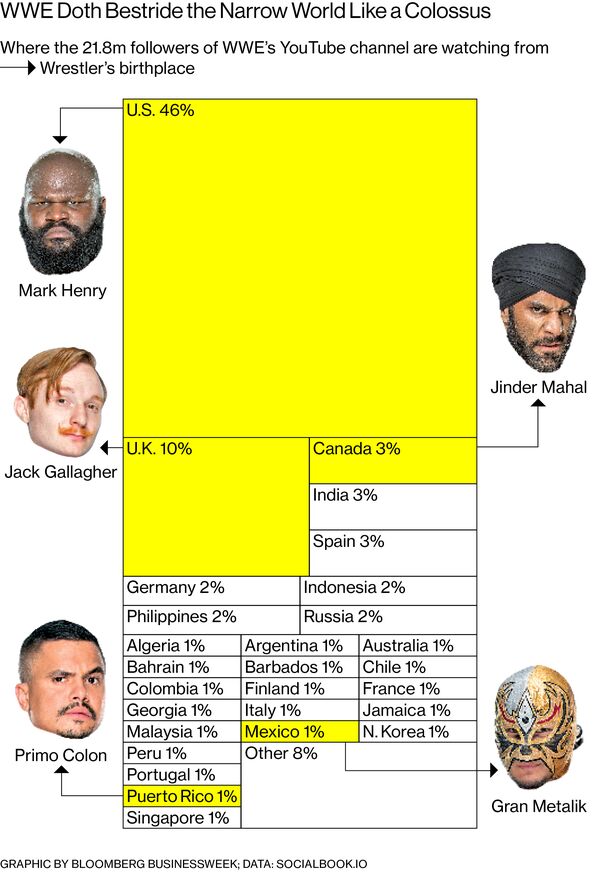

With a growing cast of female and international wrestlers, WWE is now plotting to expand its fan base beyond American men. It already has loyal followings in certain overseas markets, but executives say the spread of streaming video and social media has created the perfect conditions for an all-out global invasion. Over the past year, the company has teamed up with streaming service PPTV to offer the WWE Network in China, staged an international talent tryout in Dubai that drew aspirants from 18 countries, put on a 10-day European tour, and teamed up with Fox Sports Mexico to create a Spanish-language show that’s airing throughout Central America and the Caribbean.

Overseas audiences account for 70 percent of WWE viewing, McMahon says, yet only 30 percent of its revenue. “So there’s a big opportunity.”

WWE is a tightly scripted company. Everything that happens in and out of the ring is by design. The announcers, executives, and wrestlers are constantly imbuing the minutiae of its ever-shifting plotlines with an overarching sense of momentousness, often by playing up the various ways WWE is “making history.” If a wrestler wins a particular title for the first time, the occasion is “historic.” If a matchup features a new twist on an old wrestling format, it’s historic. Special guest referee: historic. Novel promotional poster: historic.

In December, when WWE staged two days of live matches in the United Arab Emirates, the incantations of history-in-the-making were especially sustained. Executives say the company is well-positioned to generate more cash in the Arab world in coming years. WWE broadcasts its two weekly live-event TV shows, WWE Raw and WWE SmackDown Live, throughout the Middle East and North Africa via a partnership with OSN, a satellite provider headquartered in the UAE. Last year, OSN premiered a weekly show dedicated entirely to WWE highlights. Its analysis is hosted, in Arabic, by Moein Al Bastaki, a celebrity magician from Dubai, and Nathalie Mamo, a retired basketball player from Lebanon.

Roughly once a year, WWE takes its stars on tour in the Middle East and stages live, nontelevised events to stoke interest. December’s show featured a new enticement: the first women’s championship bout in the region. Inside a sports stadium in Abu Dhabi, Alexa Bliss, a pixieish firebrand whose catchphrase is “five feet of fury,” put her title belt on the line against Sasha Banks, aka the Legit Boss, a strapping, loquacious cousin of Snoop Dogg. When they’re wrestling, Banks and Bliss typically wear short shorts and cropped tops, but the UAE has strict dress codes. As a result, Banks and Bliss arrived in the ring wearing long-sleeved, ankle-hugging bodysuits designed for the occasion.

The crowd, a mix of men and women, didn’t seem to mind the historic lack of exposed midriff. At one point during the face-slapping, stomach-kicking melee, some in the audience broke out in a feel-good chant: “This is hope. This is hope.” Banks says the reception assuaged her fears that they’d be mocked and left her choked up at the thought of serving as a powerful role model for the young Arab women in the crowd. “I was trying everything in my will not to cry during performing,” she says.

“It was history-making for us,” McMahon says.

In the early 2000s the WWE’s female wrestlers were often recruited from the ranks of models, and their matches were designed to uncover skin. A “bra and panties” match could be won only by stripping an opponent down to her underwear. From 2008 to 2016, they were called divas. McMahon herself was routinely mocked by male stars such as the Rock (“Big, phony fun bags”) and jeered by crowds (“Slut! Slut! Slut!”).

She traces the shift away from this mindset to a 2015 women’s tag-team match that lasted only 30 seconds. “Our fans started a hashtag called #GiveDivasAChance,” she says. Since then, WWE has hired about 40 more women wrestlers, started calling its female performers “superstars” in concert with the men, and unveiled a championship belt with more gravitas and less decorative pink butterfly. McMahon describes the course correction as long overdue. “I never felt great about the way we portrayed our women,” she says. “It was something that I spoke up against for quite some time. But it took me a while to have a stronger voice in the room. Ultimately, the voice that needed to be heard was our fan base.”

Not coincidentally, turning women performers into more wholesome, athletic superheroes has made the product more palatable to countries with conservative values—and more appealing to advertisers wary of angry parents. “From a sponsor standpoint, they’re more socially acceptable,” says Dave Meltzer, editor of the Wrestling Observer Newsletter. But, he adds, “there are people who complain to me constantly that they want it like it was back when it was really, really raunchy.”

Globalization has complicated these storylines. As WWE’s overseas ambitions have grown, so has its need to recruit wrestlers of diverse ethnicities and national origins—and to have some of them perform as heroes. “Forty percent of our talent roster is international,” McMahon says. “We’re looking to grow that.” The jingoism hasn’t entirely disappeared, but the us-vs.-them dynamic has become less clear-cut.

“If you did what you did in the ’80s now, it wouldn’t feel right,” says Meltzer. Thanks to YouTube, he points out, foreign wrestlers can gain sizable followings before ever appearing on WWE. And in general, fans today care more about the quality of moves in the ring than the acting outside of it. Fluent acrobatics, he says, matter more than fluent English.

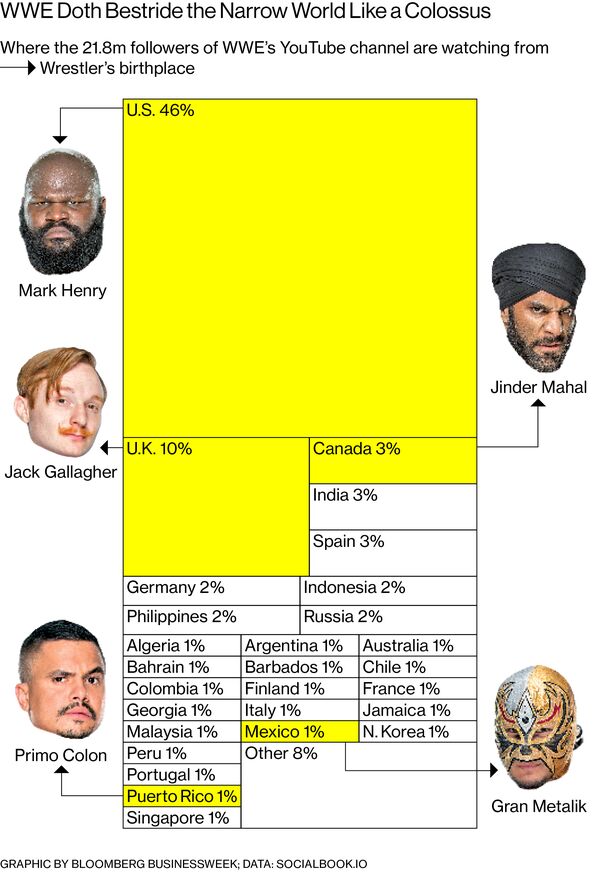

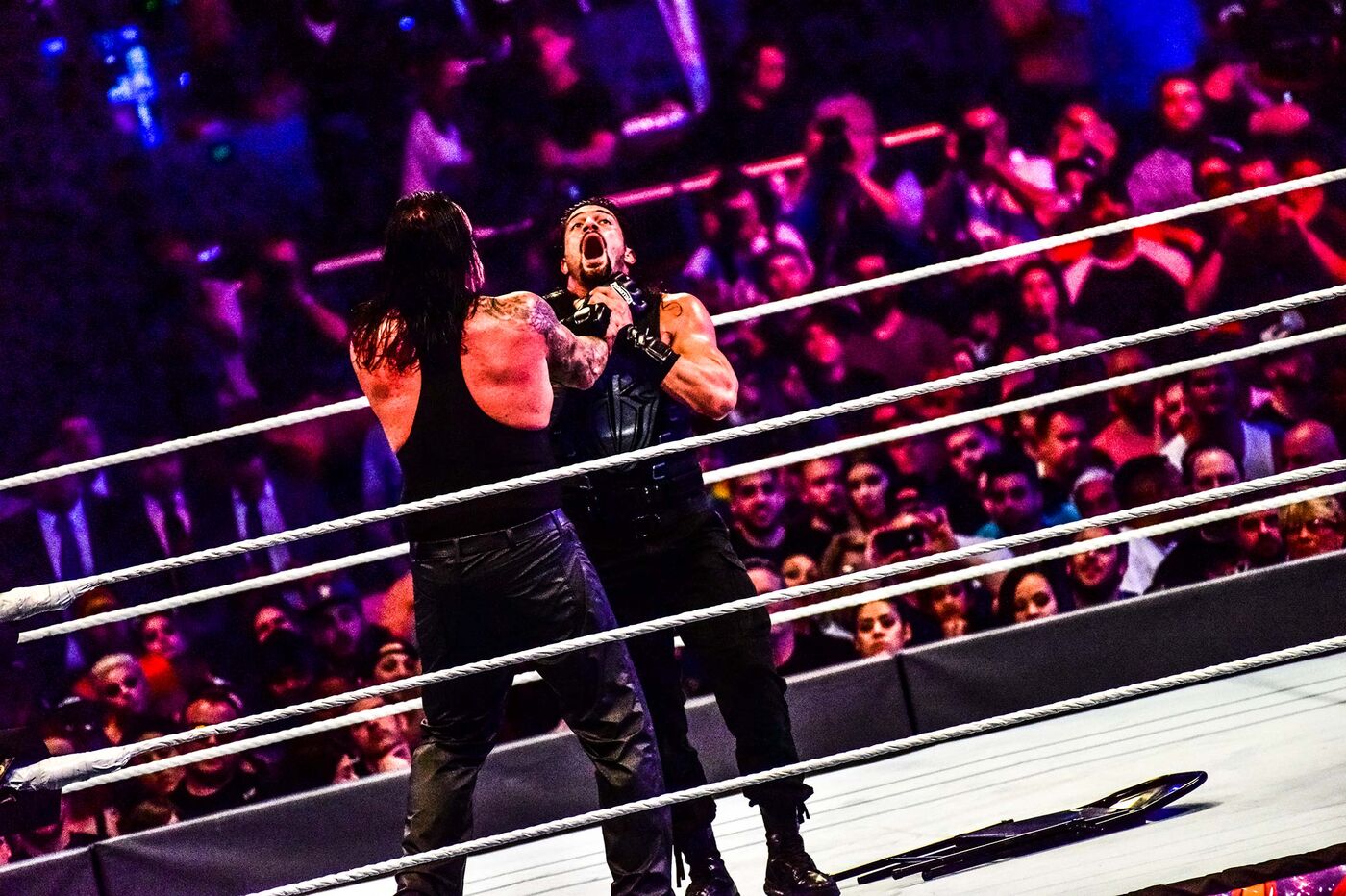

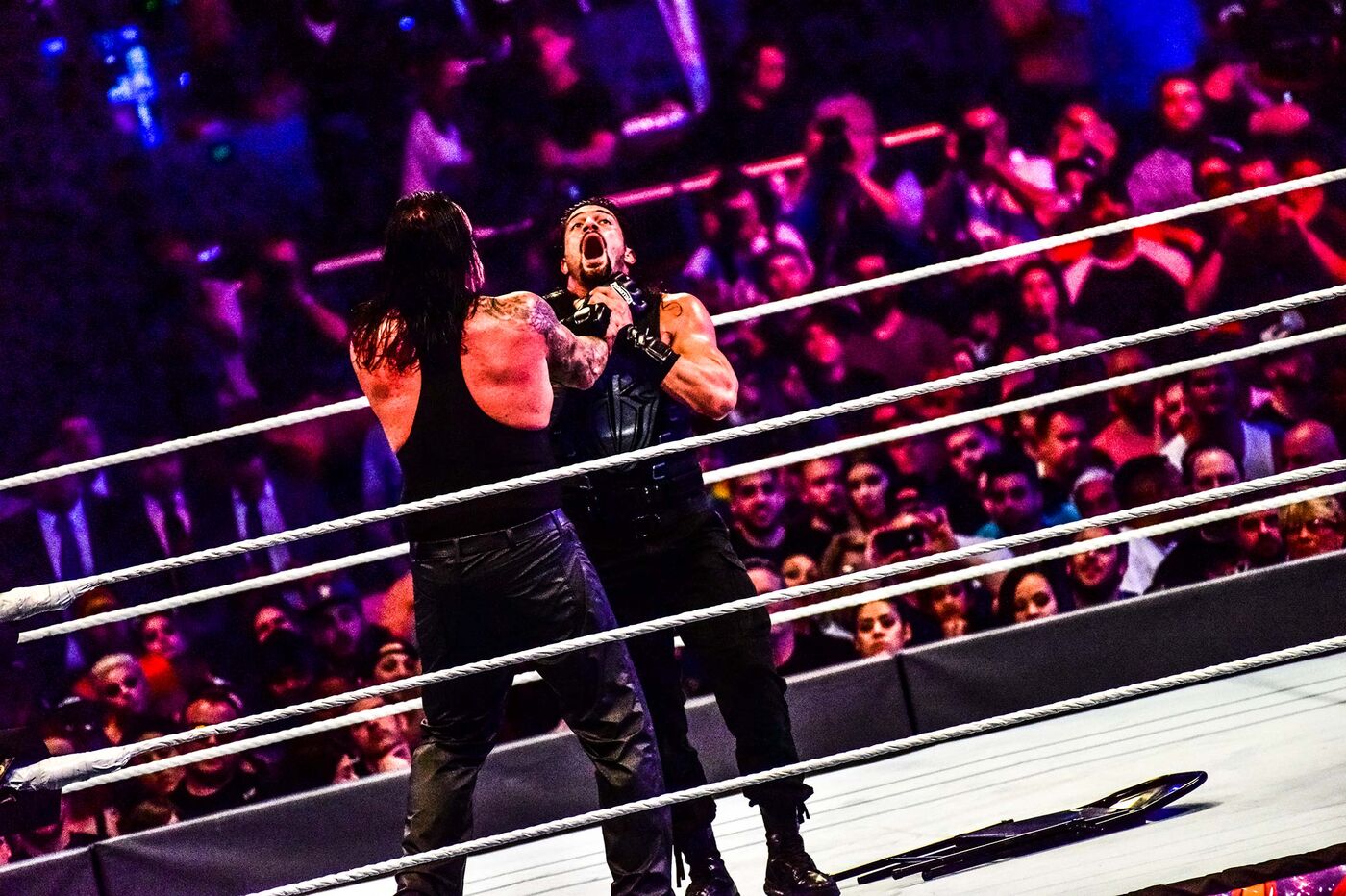

This dynamic has played out with India, for example, where company executives say WWE is the second-most-consumed sport after cricket. Last May, Jinder Mahal, a glowering knave with a flair for neckbreakers, was crowned WWE champion, the first of Indian descent. (Mahal, who is Canadian-born, held the title for several months before losing it to A.J. Styles.) In December, at a live exhibition inside a stadium in New Delhi, Mahal shed his turban and wrestled Triple H in front of a frenzied crowd that the Times of India estimated at 8,000. Ultimately, Triple H prevailed. Afterward, he shook hands with Mahal, said it was an honor to wrestle the “Modern Day Maharajah,” and joined him for some in-ring Bhangra moves. The détente was short-lived, though. Before exiting, Triple H pancaked one of Mahal’s minions, heightening the drama for a potential rematch. Your move, cricket.

Such events have helped the WWE Network lift its international subscriptions from 44,000 after its first year to roughly 410,000—a level of success that was far from certain when it began in February 2014. At the time, it was unclear if anybody anywhere would pay for a stand-alone pro wrestling network. Most subscription video apps were aggregators such as Netflix, not dedicated to single brands like WWE. “There was not a playbook out there for us to say, ‘Let’s go look at how X, Y, or Z did it,’ ” says Michelle Wilson, WWE’s co-president.

The WWE Network has since evolved to include a vast bank of archival footage, marquee events such as WrestleMania, and a hefty slate of exclusive programming. Every Wednesday night, the service streams a show featuring up-and-coming performers from NXT, a developmental league run by Triple H. The WWE Network also hosts an hourlong broadcast of its cruiserweight division, called WWE 205 Live, as well as talk shows and documentaries.

Over the years, the company has occasionally had to fend off rival wrestling promotions on TV, most notably World Championship Wrestling (which it later bought) in the 1990s. To date, the WWE Network hasn’t had to face an equivalent challenge from a streaming service, though several overseas promotions are introducing rival products. Tokyo-based New Japan Pro-Wrestling Co. offers a subscription product for 999 yen ($9.20) a month, which is now available in English. New Japan has been building up its appeal to Western viewers, in part by staging a series of buzz-making matches starring WWE legend Chris Jericho.

In most of the world, however, WWE has no direct competitors. Perhaps as a result, the company seems confident it can win over local fans without investing huge amounts of money. At the moment it employs seven international general managers, scattered from Shanghai to Singapore to Australia, who oversee regional development and report to Wilson and her co-president, George Barrios. A conquering army it is not, but that might be all right, according to BTIG’s Ross. “You don’t need to put offices in every single country around the world,” he says. “You just need to make a couple of targeted bets on talent in certain core overseas markets.”

When the WWE Network made its debut, there was some concern among analysts that it might decimate WWE’s audience on traditional television. So far that hasn’t happened. With Raw and SmackDown Live, WWE continues to air five hours of original wrestling programing each week on USA Network. The ratings have remained strong even as most of cable TV has slumped, with WWE shows consistently ranking among the top 20 most popular of the week.

WWE’s current domestic deal with Comcast Corp., which owns the USA Network, is set to expire in 2019. Some analysts say WWE’s next deal will be more lucrative. The company has attracted a broader base of advertisers of late thanks to the growing demand among sponsors for live programming, plus its tamer fare. There may be more competition this time. “We would not be surprised to see tech platform bidders emerge, which have begun to experiment with sports and scripted programming,” Ross wrote in a research note. WWE already has one of the most popular channels on Google’s YouTube, and in December it announced it had sold an original wrestling series that’s appearing exclusively on Facebook.

“Facebook could be the most likely destination for WWE content in 2019,” Ross wrote.

Later this year, Vince McMahon turns 73. An aging patriarch often spells trouble for a family-run business, but the McMahon clan seems poised to endure. In 2016, after six years away from WWE, Shane McMahon, Stephanie’s older brother, returned. These days, he plays the on-screen commissioner of SmackDown Live and wrestles with a vengeance. “He is really a strong talent for us right now,” says Stephanie—though he isn’t, she points out, an actual executive at the company.

For many longtime observers, a WWE without Vince McMahon is hard to imagine. James Clement, an analyst with Macquarie Capital Inc., says that while the family has a “deep bench,” investors would be concerned if he suddenly abdicated the throne. “When there is the first wrestling match on Mars, Vince is probably going to be behind it,” Clement says.

For now, the McMahons seem content to beef up their arsenal of female and international wrestlers on planet Earth. In January, WWE held one of its biggest annual events, the Royal Rumble, at Philadelphia’s Wells Fargo Center. Backstage, before the show, Banks, dressed in sweats, rips open two bags of chunk tuna and dumps them into a bowl. The Legit Boss is nervous. “If I try to eat a real meal, I won’t be able to get it down,” she says.

The night’s biggest surprise is the unveiling of WWE’s latest high-profile hire, mixed martial arts fighter Ronda Rousey, who will become a full-time wrestler. But the outcomes of the titular events—men’s and women’s versions of a prolonged battle in which 30 combatants try to win a title shot by throwing their opponents over the top rope—raise eyebrows, too. The women’s Royal Rumble is the first-ever, an achievement whose historic nature the announcers don’t shy away from stressing. Stephanie McMahon presides ringside as a guest commentator, while other teams of broadcasters provide live commentary in Spanish, German, Russian, Japanese, Mandarin, Portuguese, and Hindi.

Banks sashays onstage in Wonder Woman-style gear as the first entrant; 55 minutes later she’s tossed out of the ring by duplicitous twins. The last wrestler standing is Asuka, a kaleidoscopically styled, fiercely kicking combatant recruited from Japan. Earlier that night her compatriot, Shinsuke Nakamura, won the men’s bout. Introduced only a few years earlier, at press conferences in Tokyo, Asuka and Nakamura will now headline WrestleMania, WWE’s biggest annual show, in front of 75,000 berserk fans in New Orleans this April. Your move, New Japan.

Bloomberg

Check out our latest video

Exploring our target industries

At Davalyn, our tenured team of niche-focused talent acquisition experts takes on the hiring challenges of a diverse and growing set of industries. Make our perspectives your most powerful recruitment and retention resource.